Storm name number ten was given when Jocelyn was named hot on the heels of Isha in what has felt like an unusually stormy autumn and winter for the UK. But why have there been so many named storms, and are there underlying factors at play?

A stormy season so far

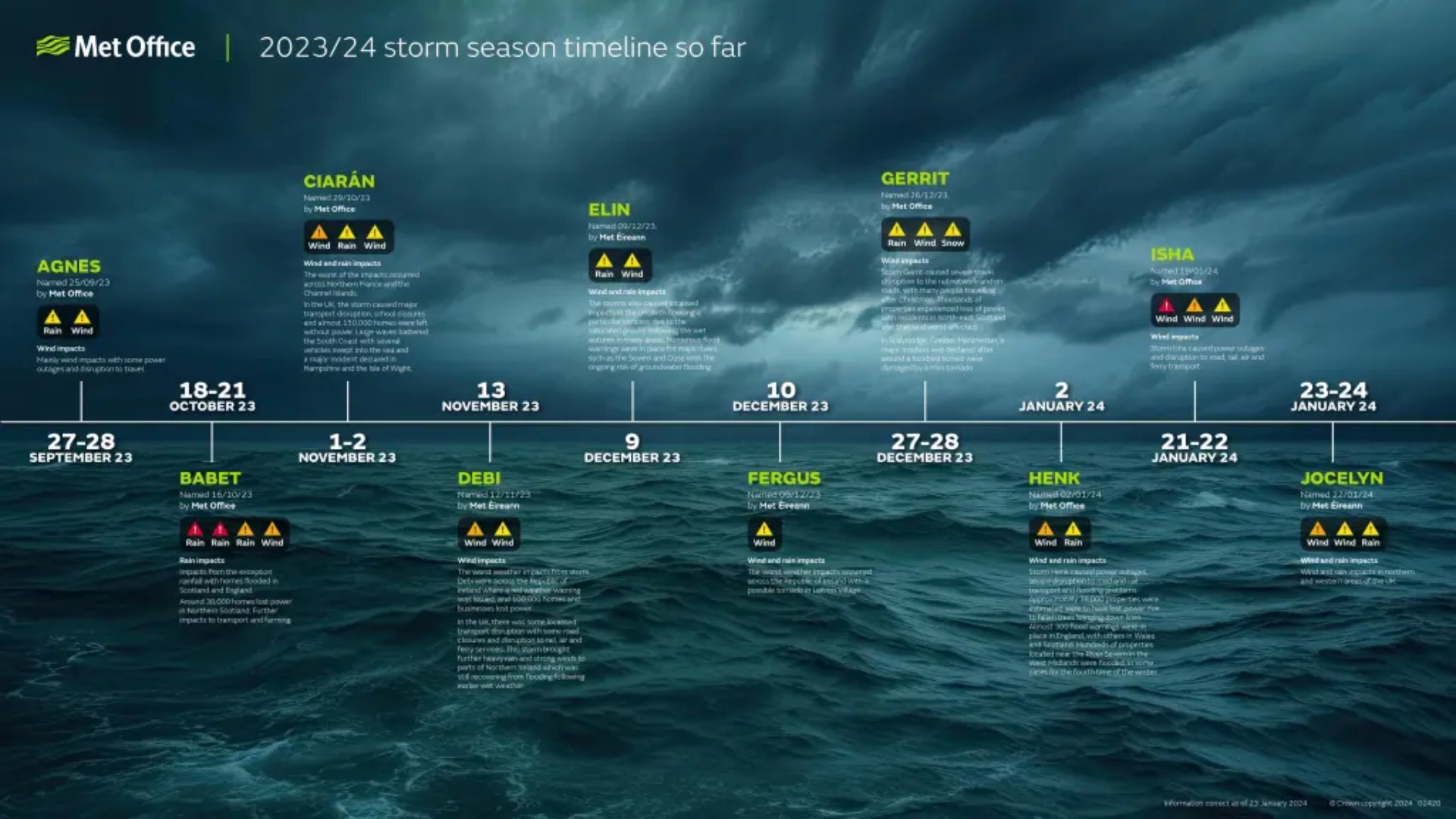

Storm Jocelyn is the tenth storm named since 1 September 2023 by the Met Office’s storm naming group, which includes Met Eireann and KNMI.

The storm name season runs from 1 September to August the following year, with a new alphabetised list of names released at the start of September each year.

Since storm naming was introduced in 2015 to improve the communication of severe weather events, the furthest through the list the group has got is to Storm Katie, which impacted the UK in March 2016.

2023/24’s storm naming season is now just one name away from equalling 2015/16’s number of named storms, with over seven months still to go until the list is reset again.

What’s behind the storms this year?

Storms are named when they’re likely to cause ‘medium’ or ‘high’ impacts in Ireland, the UK or the Netherlands. They’re named to raise awareness of severe weather and help people to prepare themselves so that impacts can be minimised.

To look at why the last few months have had a stormy theme, we need to look at one of the drivers of the UK weather; the jet stream.

Met Office Meteorologist and Presenter Annie Shuttleworth explained: “While we have had some drier and calmer interludes, the stormy nature of the UK’s autumn and winter so far is chiefly dictated by the position and strength of the jet stream, which is a column of air high up in the atmosphere.

“The jet stream greatly influences the weather we experience in the UK and during recent months this has largely been directed towards the UK and Ireland, helping to deepen low pressure systems. These systems have been directed towards the UK and have eventually become named storms due to the strong winds and heavy rain they bring.”

More recently, a pool of very cold air has sunk southwards across North America. The temperature contrast here has intensified the jet stream influencing the development of Storms Isha and Jocelyn.

What’s the trend in named storms?

As storms have only been named by the Met Office since 2015, using the storm name list to assess the impact of climate change isn’t statistically robust because the time period is far too short. Climate scientists typically use long-running datasets that compare decades and centuries to assess the impact of human emissions on long-term weather and climate trends.

In addition, storms are named by meteorological organisations subjectively based on their likely impacts, so it’s not an objective observation-based dataset in terms of measuring the effects of climate change.

One reason people might perceive there to be more storms could be the increase in media and social media coverage when impactful weather is around compared to historical weather events.

However, the Met Office’s long-term climate statistics do give a view of impactful weather in the UK in previous decades.

Climate change and windstorms

If you ignore the introduction of named storms in 2015 and look at the longer term Met Office UK climate statistics, it remains hard to detect trends in the number and severity of wind events in the UK.

Dr. Amy Doherty is Science Manager of the National Climate Information Centre at the Met Office. She explained: “The UK has a history of impactful storms stretching back hundreds of years, long before the introduction of named storms in 2015.

“One thing that is clear from observations is that there’s big variability year-to-year in the number and intensity of storms that impact the UK. This large variability is related to the UK’s location at the edge of continental Europe and relatively small geographic size, so small changes in the position of the jet stream – which puts us in the path of low-pressure systems – can make a profound difference in the weather we receive.

“This large variability means that we have to be particularly cautious when analysing the data. In our observational records, it’s hard to detect any trend one way or the other in terms of number and intensity of low-pressure systems that cross the UK. While our climate overall is getting wetter, there are no compelling trends in increasing storminess in recent decades. Recent stormy seasons – such as that of 2013-2014, before the storm naming system was introduced, clearly illustrate the fundamental problem with drawing conclusions from a simple count of the number of named storms.”

Most climate projections indicate that winter windstorms will increase slightly in number and intensity over the UK as a result of climate change. However, there is medium rather than high confidence in this projection because some climate models indicate differently. Year-to-year variability in storm frequency and intensity will also continue to be a major factor in the future climate. We can be confident that the coastal impacts of windstorms, from storm surges and high waves, will worsen as the sea level rises.

More storms to come this year?

After Storm Jocelyn this week, the UK will continue to see spells of wet and windy weather, especially in northern and western areas. Long range models suggest that late January and early February weather could see some drier interludes further south, while wet and windy weather remains possible in the north and west.

In terms of what this means for named storms, it’s too early to pick out when the next one might be, but there remains a chance of further impactful weather as we move through meteorological winter and into spring.

Find full information on storm name seasons from the Met Office since their creation in 2015 at the UK Storm Centre.