UK and Global extreme events – Heavy rainfall and floods

Determining the likelihood and severity of extreme events for the past, present and future.

Rainfall across the globe is determined by two things:

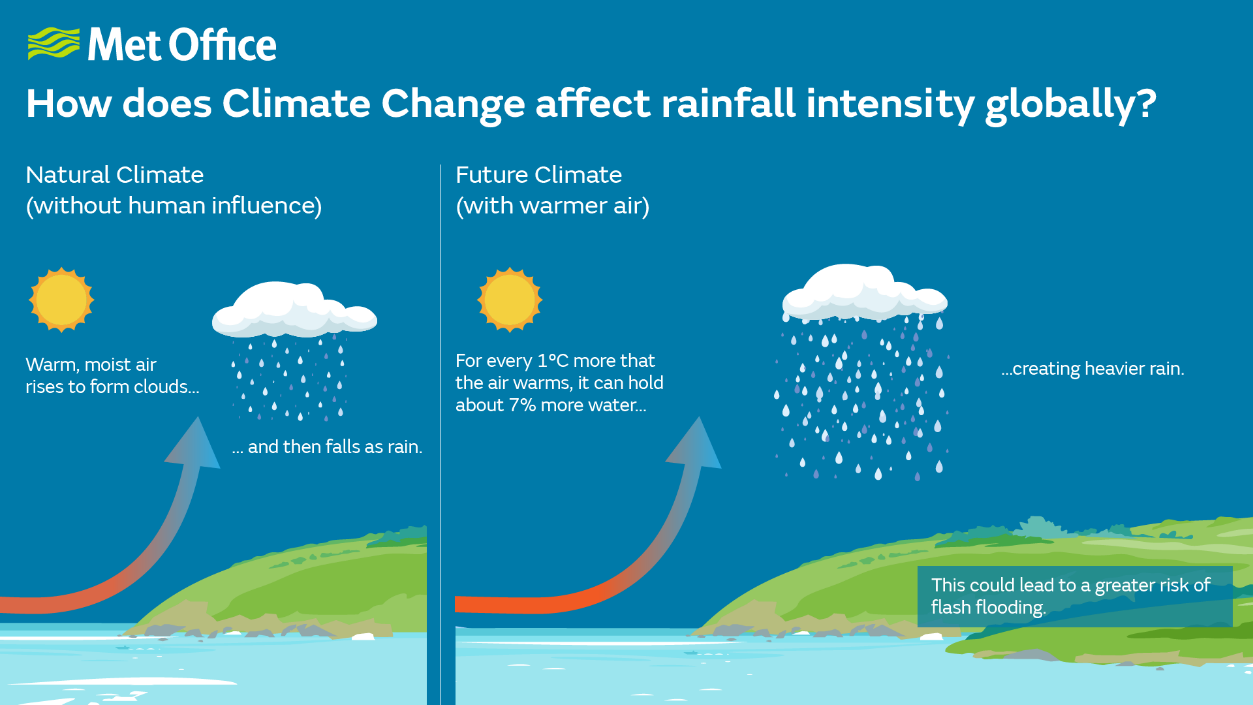

- How warm the air is

Hotter air can hold more moisture. If the air has an unlimited water supply, such as an ocean, then warmer air draws up extra moisture. This results in clouds containing a greater number of larger rain droplets, and can be why showers in summer are often heavier than in winter. As the climate continues to warm, the effect will increase, and heavy rainfall events are expected to become more common. - The movement of weather patterns across the world

For example, the position of the jet stream near the UK influences a lot of our weather. However, any shifts in these weather patterns will lead to some regions becoming drier and others becoming wetter.

Warmer air under climate change can create heavier rain.

By understanding how our changing climate affects these systems regionally, local governments can better prepare for changes to rainfall in the future.

UK observations

The latest State of the UK Climate report indicates the UK has become wetter over the last few decades, although with significant annual variation. 2011-2020 was 9% wetter than 1961-1990.

The change in rainfall depends on location – for example, Scotland has experienced the greatest increase in rainfall, while most southern and eastern areas of England have experienced the least change. From the start of the observational record in 1862, six of the ten wettest years across the UK have occurred since 1998.

The number of days where rainfall totals exceed 95% and 99% of the 1961-1990 average have increased in the last decade, as have rainfall events exceeding 50 mm. Both these trends point to an increase in frequency and intensity of rainfall across the UK. However, the variation in rainfall from year to year is still large, highlighting the importance of considering long-period natural variations.

Because current trends in extreme rainfall are within past natural variation, it can be difficult to isolate effects on our longer-term rainfall due to human influence by looking only at the observational record. A study using high-resolution climate models predicts that the influence of human-caused climate change will likely not be seen clearly in short-duration (hourly and shorter timescale) extreme rainfall trends in the UK until at least the 2040s for winter and 2080s for summer.

In the meantime, it is possible to determine how much human-influenced climate change has affected significant events through climate attribution studies.

While it is also useful to study the impacts of increased rainfall, tracking flooding events caused by extreme rainfall is much trickier. Flooding can be affected by a combination of many factors including (but not limited to) river flow rates, local soil type and the presence of flood defences.

UK projections

Rainfall patterns in the UK vary by region and season and will continue to do so in the future. The latest set of UK climate projections (UKCP18) provide the most up-to-date assessment of how the UK climate could change over the 21st century.

Climate projections indicate that on average, winters will continue to become wetter and summers drier, though natural variability will mean we will continue to see individual years that don’t follow this trend.

However, rain that does fall in summer will likely be more intense than what we currently experience. For example, rainfall from an event that typically occurs once every 2 years in summer is expected to increase by around 25%. This will impact on the frequency and severity of surface water flooding, particularly in urban areas.

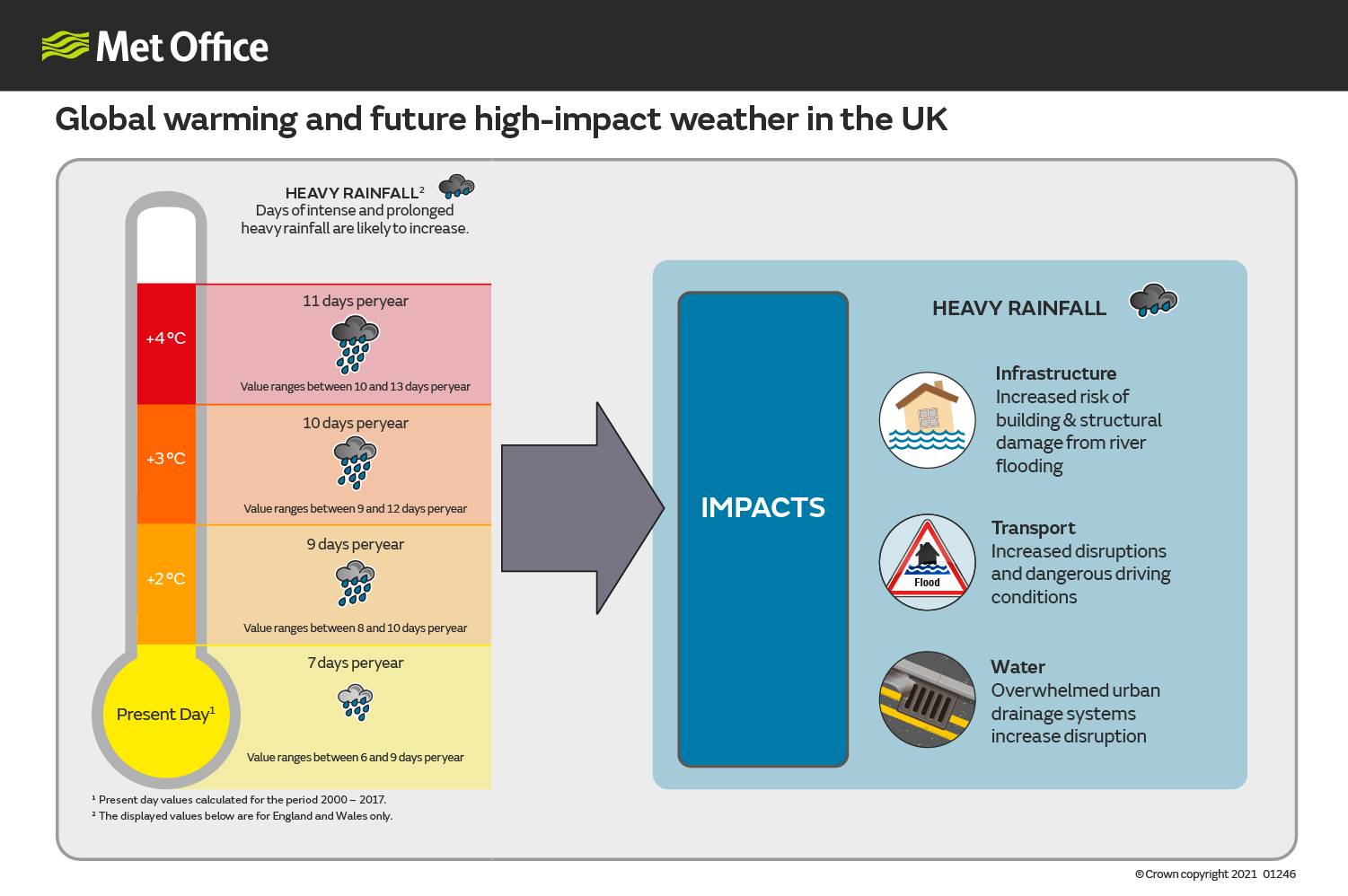

As global temperatures rise, the number of extreme rainfall days is expected to increase. Data available here.

As global temperatures rise, the number of extreme rainfall days is expected to increase. Data available here.

However, an increase in severe flooding is not necessarily a certainty by the end of the century. By significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions and using a combination of natural and man-made barriers, the worst effects of flooding in the future can be lessened.

The Environmental Agency has published The National Flood Resilience Review, setting out a combination of short-term and long-term projects to mitigate flooding based on different futures under climate change.

Global observations

The Sixth Assessment Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded it is likely (over 66% probability) that average precipitation has increased since 1950 with a faster rate since 1980. The number of heavy precipitation events over land has likely increased in more regions globally than it has decreased, with confidence highest for North America, Europe, and Asia where there are more observations.

There is currently very low confidence on trends for extreme rainfall lasting less than a day due to a limited number of observations and studies.

Heavy rainfall over land has increased, likely due to human influence.

As for what has caused these changes, it is likely human influence contributed to global-scale changes in rainfall patterns over land since 1950. It is also likely human influence has led to an intensification of heavy precipitation, with high confidence across North America, Europe, and Asia.

Because fluvial flooding is affected by more than just rainfall, as described above, there is low confidence that human-caused climate change is having a direct influence on the frequency and scale of flooding globally.

Global projections

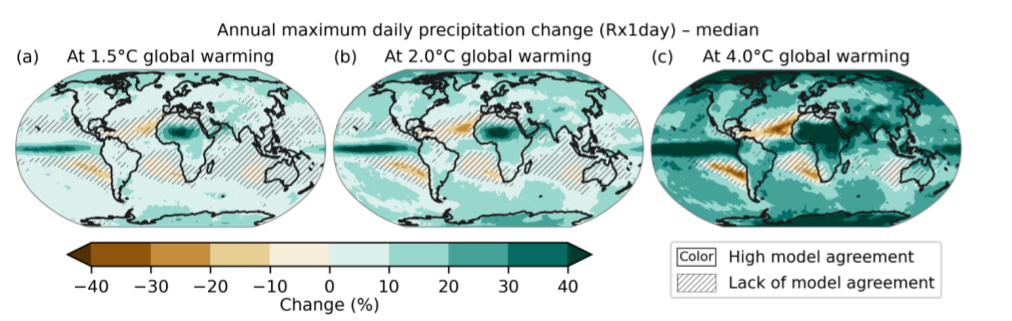

Changes in rainfall patterns will vary across regions. It is very likely (over 90% probability) that latitudes close to the poles and tropical oceans, and likely that monsoon regions will see an increase in overall rainfall. However, large parts of subtropical regions will likely see a decrease in rainfall, leading to drier conditions.

For short-duration extreme rainfall events, such as thunderstorms and showers, more intense individual showers and fewer weak rainfall events are likely as temperatures increase.

If global warming increases to over 4 °C above pre-industrial levels it is virtually certain (over 99% probability) that very rare heavy precipitation events (1 in 10 or more years) over most continents will become more frequent and intense than the recent past. This is less likely at lower warming levels.

Projected changes in annual maximum daily precipitation at (a) 1.5 °C, (b) 2 °C, and (c) 4 °C of global warming compared to the 1851-1900 baseline. Most areas are set to see increases. Source: IPCC Sixth Assessment Report Working Group 1.

Related pages